Retablo di Tuili

The Retable of Tuili is the most complete work among those conserved and painted by Joan Barceló II (former Master of Castelsardo) around 1500. Its impressiveness and artistic qualities allow us to analyse the figurative language of the master, who marks a turning point in his pictorial production with this retable. In the polyptych, as never before, it has been possible to reconstruct the figurative genesis that is largely based on models widespread in the northern European sphere, Flemish and Germanic in particular, grafted onto the varied Catalan-Valencian substratum of the end of the century.

The entire figurative apparatus, suitably reinterpreted and customised with the stylistic characteristics of the master, is constructed and composed keeping in mind the current language in European workshops that made Flemish painting an obligatory but not exclusive reference.

….

But it is the Roman Emperor himself to reserve us some surprises, for it is a precise rendering of the King of clubs taken from the plate engraved by the so-called Master of Playing Cards.

….

The prints analysed so far belong to a circle of engravers that somehow marks the final stages of late Gothic production. They belong to the artistic climate that generated the Tuilese Retable. … The first engravings by Albert Dürer circulated in Sardinia in 1505. It is surprising to discover that even before that date Joan Barceló II introduced copies of Dürer’s prints into the production of the Tuili Retable. In particular in the Calvary, some figures … are taken from two xilographies: the Great Crucifixion, 1496 and the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, 1500.

… the dates of the realisation of the Retablo di Tuili lie between 1496, the year the Dürer print was made, and 1500, the year the census for the payment of the retable was stipulated.

…

This continuous interweaving of models that, coming from different sources, are inserted and repeated in Joan Barceló II’s works, becomes a characteristic note of his working method and demonstrates once again that the workshop he directed was undoubtedly of the highest order in the Mediterranean artistic context.

Quotations from

Enrico Pusceddu’s essay Joan Barceló II (former Master of Castelsardo). Issues in painting in Sardinia around 1500

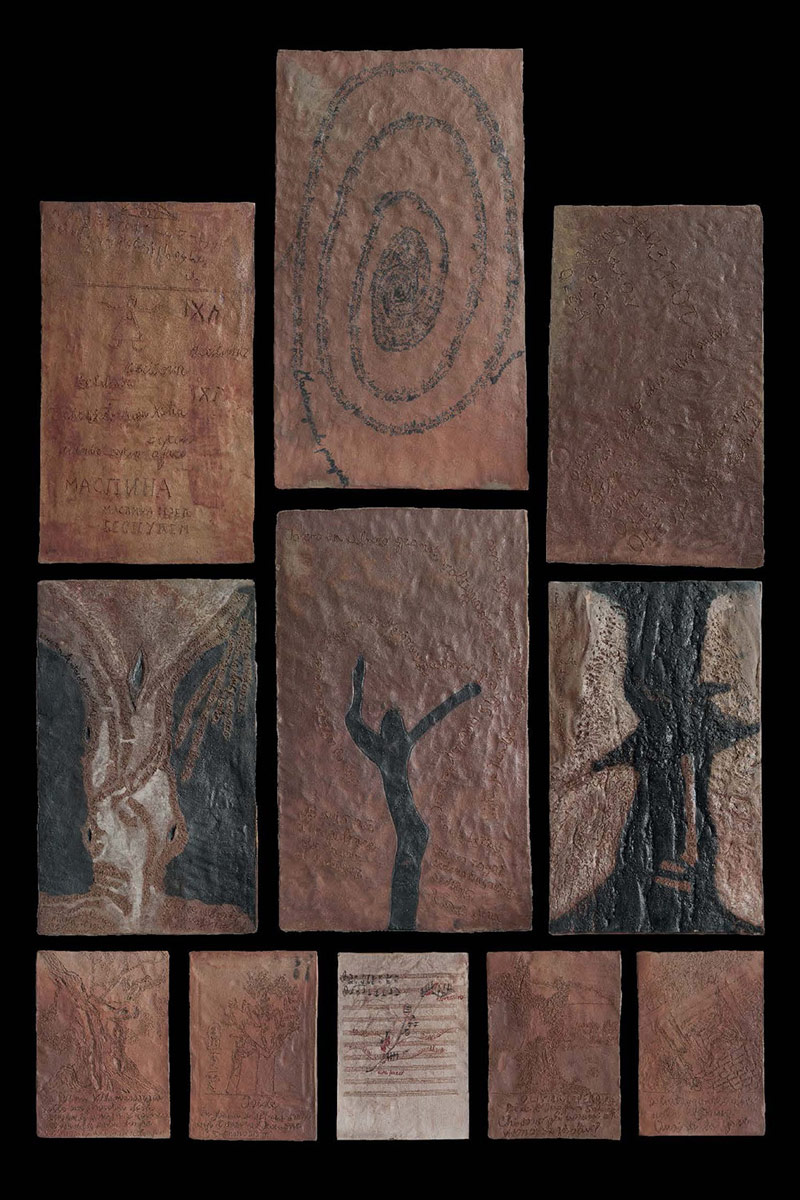

Retablo degli olivi

Historica and procedure

Caught in a sudden thunderstorm, I went inside the Church of San Pietro to take shelter, in the village of Tuili, Marmilla region, in the heart of Sardinia. In the dimly lit I was attracted by the gilding of the wood as it was in its original function: shining. In this way discovered the Retablo di Tuili by the Maestro of Castelsardo (1500). I stood there and looked at it for a long first time, until it bled. Then I returned there many more times.

At that time I was looking for a form that could include in the same visual space, different languages, and the form of the retable appeared to me as the page of the imagined book.

Of the original retable, many characteristics have been preserved. First of all, its making in the workshop. The change of materials corresponds to the change of skills of the working group. So the central figure is the shadow of the sculpture of the Armenian artist Jora, Vacuna.

One of the bas-reliefs was made by the Kurdish-Syrian calligrapher poet Golan Haji, who also added, in the spiral of central engraved olive tree names, some Syrian cultivars and some fantastic species.

The white background panel is the main motif of the original composition for a five-voice chorus on the names of olive trees designed by Algerian composer and calligrapher Salim Dada, the bas relief was esecuted by me.

And again, as in the original structure, there are ancient, true, magical and contemporary olive stories in the predella. Even in the absence of polverolos, the gilding here was produced by wood-fired flames at 1280° in the single-firing itself.Engraved writing defines the forms. The pattern is created by the uncertainties of calligraphy: air passes between words.To an intimate writing correspond a personal “reading” of the boards, page front to back, is entrusted to the individual illumination of a candle, placed on a small piece of crock. The shadow of the relief of the engraved words makes them stand out one by one. The firelight that saturates the surface, and which, in daylight makes it glow, is absorbed by the darkness. By following one word after another it is possible to understand the meaning of the fragments, but also to lose the form by immersing oneself in it. One must consider that writing “is painting of light and dark,” as Lomazzo wrote.

The pure color of fired clay and oxides reveals, in the gesture of engraving, the signs of buried languages that continue to nourish the living, and in turn be alive through the parlance of today.