Tudo azul, azzurro, șini asmani

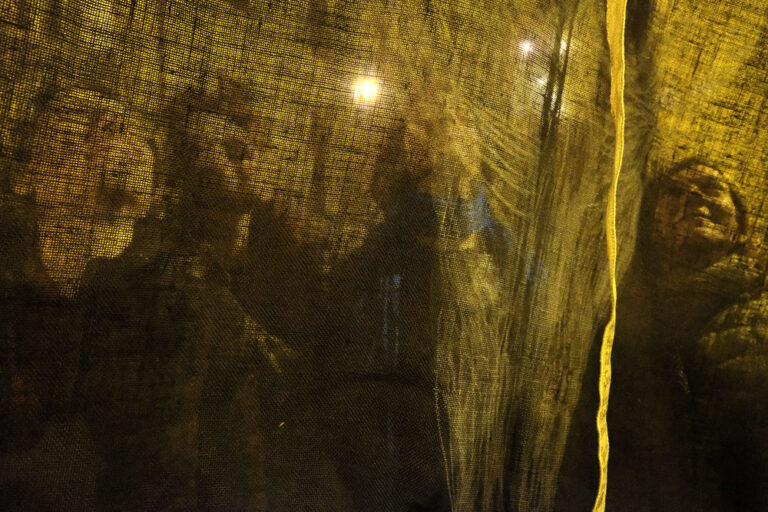

Media: blue burlap 240X160 cm, black jute 200 X 160 cm, 52 silvered papers of different size, raw burlap tapes with nineteen and thousand names written on them.

Looped sound support: a voice reads thousand of Kurdish female names

Ropes with which the two canvases are hung

mixed media

This work is especially dedicated to the memory of nineteen Yazidi girls who, on 1 June 2016, were burnt alive, in an iron cage, in a square in Mosul (Iraq) by Daesh militants, for refusing to become sex slaves. It is also dedicated to the thousands of Yazidi girls who are still imprisoned.

Não sei, comigo vai tudo azul

Contigo vai tudo em paz

Vivemos na melhor cidade

Da América do Sul

Caetano Veloso, Baby 1968

Now that you are with me tudo azul

With you all is at peace

Living in the best city

Of South America

The Brazilian expression “tudo azul”, literally meaning “everything is blue”, is equivalent to “everything is fine”. For the dictatorship in the 60s and 80s this was the meaning. For the Brazilian people it was at the same time ironic, as as in Caetano Veloso’s song, and imbued with a sense of hope, of liberation from black into azure, just azul.

Azul covers the ashes of the nineteen girls, as delicate as a wing. The dead girls return in the word șini asmani, which in Sorani, the language spoken by Iraqi Kurds, corresponds to azul. It is opposed to black.

Glances that continue to dwell in the light as from the beginning of time. Light is the memory that nourishes the horizon, on which traits of faces and bodies converge, ours and those belonging to the earth. In the light the girls’ faces

will take the features of those who will meet their gaze in the silver cards.

(detail, one of the silver card, ph. Rosi Giua)

SPACE, ACCESSIBILITY, TIME, CARE, MANAGEMENT OF STREET INSTALLATION

Tudo azul, azzurro, șini asmani is a work/installation designed for the street.

SPACE

It was installed in a natural pedestrianized square in downtown Cagliari. Plenty of space to be able to walk around the installation, to allow many people to stop at once.

ACCESS

Access to the work was totally free: bicycles, wheelchairs for the disabled and baby carriages, walkers for the elderly and benches for sitting. No captioning of the installation. Writing can be an obstacle, especially in an alphabet that is not one’s own. There was a woman’s voice on a loop calling out Kurdish female names, which allowed access to part of the installation for the visually impaired; for the hearing impaired, the thousands of names were written on burlap ribbon, part of the installation. In the act of naming, of continuing to call the girls and women, they cease being numbers: each becomes a ‘person’, in the original meaning of ‘sounding through’, referring to the stage mask that emphasised the character’s distinctive features. Here and now, being an individual, within a genocide.

CARE

So you can do care without writing.

The idea of sharing (for a very limited time, many hours but only on a single day) installations made with techniques and media generally considered “not suitable” to be exhibited in the open air, such as graphite or tailor’s chalk on burlap.

Naked installations, without any protection. This is one of the elements that opens toward those who pass by: there is a trust inherent in this gesture that leads to a desire to “take care of it,” to become its curator in all senses. Each of those who pause is a curator in their own way. Thus there is not just one “care” or “curation” but as many curators as there are people who stop. What was common to all who curated the installation is that not one felt the need to take a photo with their smartphone. The curators’ ages ranged from 1 to 90.

MANAGEMENT OF THE CURATORS

Some women gave me money. I asked them if it was meant for the Yazidi girls (to whom I later intended to send it anyway) and their response was interesting. No, these are for the artist to take this installation around. Two girls who stayed for a long time, maybe longer than all the others, stqarted giving me money; other women followed suit. A first reflection on what generated this action can be: taking care also means that: to feed the work, to partake of it.

VIDEO

The gaze of Rosi Giua is in her hands, in her video she captures some of all these moments with her sensitivity.

Photo and video Rosi Giua